It is no question that the meteorological community has lost the faith of the public, given recent forecasting gaffes with Potential Tropical Cyclone Two (PTC2, eventually becoming Hurricane Bonnie) in June and Invest 98L (eventually becoming Hurricane Ian) in September this year.

Both events were complex. The forecasts, alerts, watches, and warnings were ultimately based on the latest numerical weather prediction models and data. Both the National Hurricane Center and the Trinidad and Tobago Meteorological Service erred on the side of caution.

Though impacts were not as widespread as initially anticipated, Grenada suffered hurricane-force wind gusts and damage with PTC2, while northeastern Trinidad experienced significant floods and landslides due to Invest 98L. We also saw a widespread mobilization of flood mitigation measures ahead of PTC2 and similar preparedness actions ahead of Invest 98L.

However, many other forecasts have primarily played out as expected for much of this year, including the high-impact rainfall and landslide event of Invest 91L moving across T&T, causing upwards of 500 inclement weather reports across both islands and taking one life.

Still, with the past blunders, many have taken weather forecasts with a grain of salt. It certainly doesn’t help when other social media actors take to Facebook to declare “life-threatening flooding” for a longer-range event where models are still in disagreement.

This article is not intending to criticize nor make excuses for past forecasts that never came to fruition. Instead, we hope to educate about the complexities of forecasting and the uncertainties within a forecast.

Understanding forecasting

Weather forecasts are created using data about the current state of the atmosphere and the understanding of atmospheric processes (meteorology or atmospheric science) to predict how the atmosphere will evolve. Because our meteorology knowledge is still incomplete, and the atmosphere is inherently chaotic, forecasting is not simple.

A weather forecast first looks at the current weather conditions and the features in the atmosphere that is producing them. Meteorologists use a large quantity of data, including surface observations of temperature, winds, humidity (to name a very few), satellite imagery, radar data, radiosonde (a profile of the atmosphere) data, upper-air data, aircraft and ship observations, and sometimes, by simply looking outside.

These millions of data points globally are ingested by supercomputers, capable of doing billions of operations in seconds, producing numerical weather prediction models. Different models use varying mathematics and physics and operate on different scales to produce outcomes. Some models have ensembles, which use the same underlying science but other initial data points to create probable future results.

A meteorologist then uses all the past, present, and future data to create a weather forecast. But given the fluid nature of our atmosphere, these data points are constantly changing. The changes in initial data (or more data) can result in substantial changes in model predictions and forecasts.

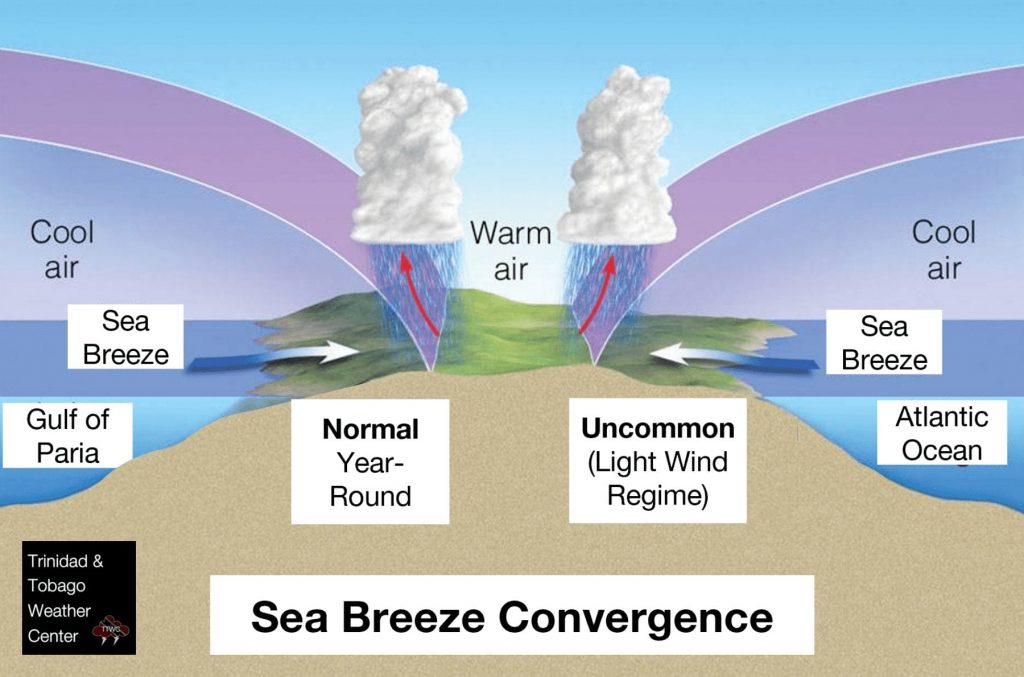

Global or regional model outcomes are not always a perfect fit for small islands like Trinidad and Tobago, where local dynamics such as topography, sea breezes, and land use influence the atmosphere.

More importantly, the further away from the present a model tries to predict, the certainty or likelihood of that outcome drastically decreases. This is why we discourage posting longer-range models, even with disclaimers of “MONITOR,” because long-range model outcomes have significant uncertainty and unnecessarily create panic for systems that have not yet formed.

Interpreting the forecast

A forecast is issued. Now what? To fully appreciate a forecast, it would be difficult to encapsulate all the necessary pieces without making this already lengthy article longer, so we’ll focus on the hazards.

Because Trinidad and Tobago, particularly during the Wet Season, is susceptible to rapidly developing and locally strong showers and thunderstorms, you usually see the following advisory attached to many of the forecasts:

Gusty winds and street/flash flooding are likely near heavy downpours!

Trinidad and Tobago Meteorological Service

Reading the same advisory daily can reduce its effectiveness, but it doesn’t mean the hazards are not present daily. When you see this, wind gusts in excess of 45 KM/H are forecast in heavy showers or thunderstorms, capable of downing trees, utility poles and lines, and causing roof damage. It also means drains can become temporarily overwhelmed, causing street flooding, and smaller water courses could temporarily overtop (flash flooding).

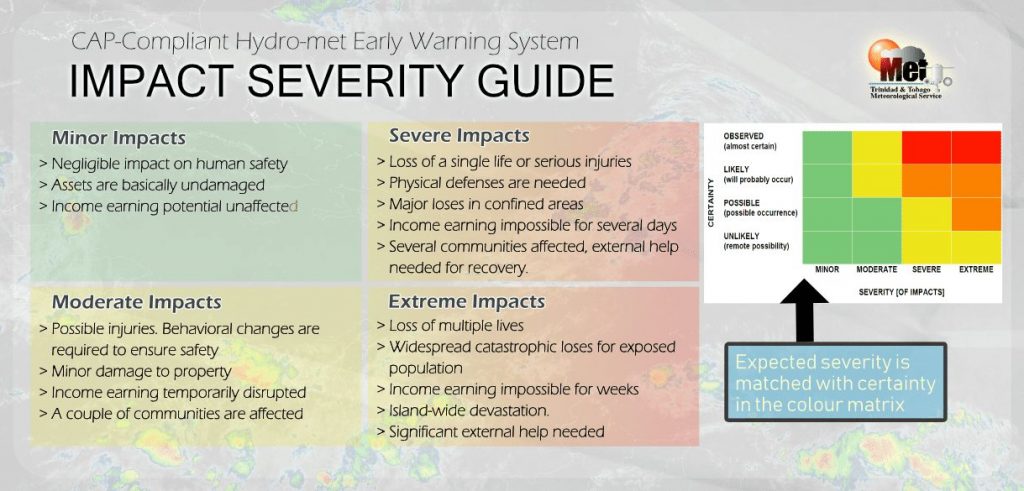

For a more severe weather event, the Trinidad and Tobago Meteorological Service may issue different variations of weather or flood alerts. From the severity of impacts, the certainty (or likelihood) of the event and impacts, the description of the hazard to instructions on how you should react or prepare – these alerts have a wealth of information that can shape your response to the event.

However, the effectiveness of these alerts remains another topic.

In our weather updates, we include the likelihood of flooding (and different flood types), the likelihood of gusty winds (as well as forecast speeds and their possible impacts), and other hazards such as the possibility of landslides, funnel clouds, etc.

Preparing for extremes, not averages

Trinidad and Tobago has noted a change of generally drier overall conditions in the age of climate change. Still, when the rains come, they come with extremely heavy rainfall rates over a short period. Flooding has become the norm with these heavier showers or thunderstorms, with underdeveloped drainage in urbanized areas and increasingly impermeable land due to land use changes for housing and infrastructure development.

We are in an era where the average rainfall or temperatures no longer apply. Instead, we have begun to experience (relative) extreme heat and record-breaking rainfall across both localized and wide areas of Trinidad and Tobago. Places that have not flooded in decades, or ever, have experienced all types of floods in the last five years. Based on this fact, Trinbagonians should remain vigilant when inclement weather is forecast, even though the forecast may change.

Remaining weather aware and weather-ready are integral in limiting the loss of lives, livelihoods, and property. Knowing how to prepare your surroundings, home, and family ahead of severe weather can make all the difference in minimizing losses. This message has been echoed by the Office of Disaster Preparedness and Management for years, and today, we echo it as well.

A final note

Published on October 23rd, 2022

This week, Trinidad and Tobago is forecast to experience an active Intertropical Convergence Zone with a series of troughs from Wednesday, October 26th, 2022, under a very favorable atmospheric setup. Broad areas of rain, with isolated to scattered showers and thunderstorms, are forecast across both islands into the weekend. Longer-range models show rainfall continuing into next week. Ultimately, this means Trinidad and Tobago could face street/flash/riverine flooding as the week progresses, with the possibility of landslides across Tobago and elevated areas of Trinidad.

While models disagree on where the highest rainfall is forecast to accumulate, how much rain is forecast to fall, and even the length of this rainfall event, Trinidad and Tobago remains in the Wet Season. October and November are the secondary peaks of the Wet Season, and those in the country should continue to stay prepared for the Hurricane and Wet Season.