Sargassum, a stringy brown seaweed, has been wreaking havoc on the shores of the Eastern Caribbean for the last decade. While the seaweed itself plays a vital role in the biosphere, the abundance of Sargassum mats has begun to adversely affect marine and terrestrial livelihoods.

What is Sargassum?

Sargassum is a genus of large brown seaweed (a type of algae) that floats in island-like masses and never attaches to the seafloor.

Sargassum is abundant in the ocean with many leafy appendages, branches, and round, berry-like structures that make up the plant. These “berries” are gas-filled structures, called pneumatocysts, filled mostly with oxygen. Pneumatocysts add buoyancy to the plant structure and allow it to float on the surface.

Numerous species are distributed throughout the temperate, and tropical oceans of the world, where they generally inhabit shallow water and coral reefs. The genus is widely known for its planktonic (free-floating) species. Sargassum mats can be up to 7 meters deep.

Where does it come from?

Sargassum is sporadic across the North Atlantic Ocean, the Caribbean Sea, and the Gulf of Mexico. Observations suggest that seaweed accumulations favor coastal areas in the Caribbean and off Brazil during the Northern Hemisphere Summer (May through September) and near the African coast during the Northern Hemisphere Autumn (September through December).

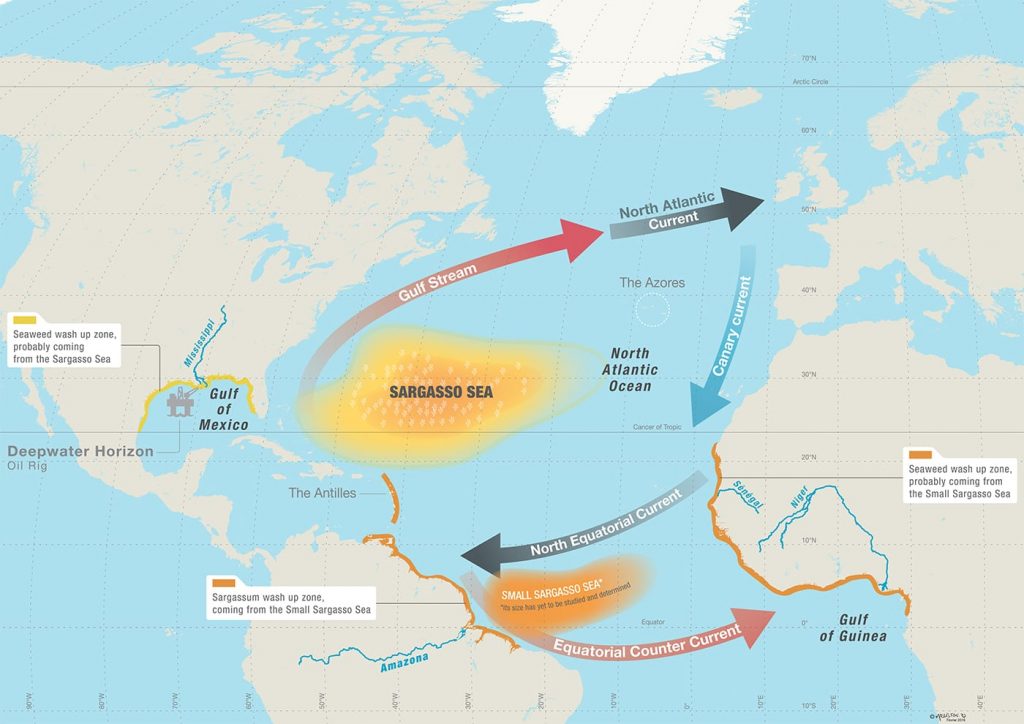

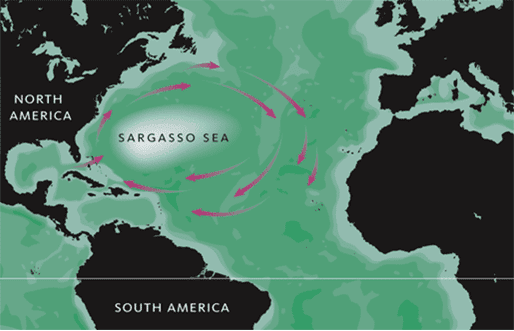

Recent research points to two areas in the North Atlantic Ocean where concentrations of the seaweed are at their highest – the Sargasso Sea in the North Atlantic and the Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt, stretching from Western Africa to the northern coasts of South America.

The Sargasso Sea

The sea is bounded on the west by the Gulf Stream, on the north by the North Atlantic Current, on the east by the Canary Current, and on the south by the North Atlantic Equatorial Current, a clockwise-circulating system of ocean currents termed the North Atlantic Gyre. Since boundary currents define this area, its borders are dynamic, correlating roughly with the Azores High-Pressure Center for any particular season.

It lies between 70° and 40° W, and 20° to 35° N, and is approximately 1,100 kilometers wide by 3,200 kilometers long. It is believed that the highest concentration of seaweed accumulates in the Sargasso Sea, named after the algae.

This area of seaweed seems to get nutrients and seedlings from the Gulf Stream, which traverse the Caribbean Sea into the Gulf of Mexico and then return to the Atlantic.

The Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt

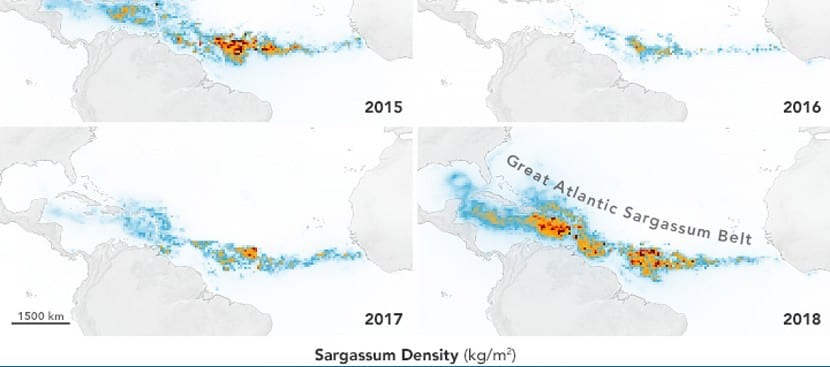

By analyzing 19 years of satellite images, researchers from the Univerity of South Florida showed that a new cluster of Sargassum developed, now dubbed the Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt, first appearing in 2011 and has reappeared almost every summer since (except for 2013). It’s also not produced by the Sargasso Sea, which lies further north.

June 2018, when the belt was at its thickest, it contained more than 22 million tons of seaweed, and stretched entirely across the Atlantic’s waters, from the Gulf of Mexico to the western coast of Africa. However, these figures are likely underestimated as the satellite data does not capture small chunks of the seaweed.

In this area, strong freshwater and nutrient discharge from the Amazon River, and stronger than usual upwelling currents near the coasts of Western Africa effectively flood the Atlantic Ocean with fertilizer for Sargassum. With moderate temperatures and the presence of a seed population that’s now become ever-present, researchers now speculate that this may be the primary source for the Eastern Caribbean’s severe Sargassum events.

Another factor that comes into play – increased nutrient content in the Amazon River, and the Orinoco River enters the Atlantic Ocean when the northern half of South America experiences higher rainfall and stronger runoff due to deforestation. One other source of nutrients – Saharan Dust.

Much of the research into Sargassum has remained limited due to a lack of data, with several conclusions remaining speculative. The Atlantic has reported more on this.

Sargassum Detection & Forecasting

The short term early warning detection for Trinidad and Tobago comes from East Coast Offshore in situ observations from platforms and ship reports, pilot reports directed to Air Traffic Control, the Trinidad and Tobago Meteorological Service, village councils and residents in coastal areas, and emergency management agencies (TEMA, ODPM).

The chlorophyll pigment within Sargassum reflects infrared light more strongly than the surrounding seawater for further offshore detection. To satellites that detect infrared, sargassum appears quite distinctly.

Hence, remote sensing and geographical information systems scientists can use optical satellite imagery such as Landsat, VIIRS, and MODIS to detect Sargassum mats and use ocean current modeling to forecast landfall.

Presently, researchers at the University of South Florida (Sargassum Watch System – SaWs) and Texas A&M University (Sargassum Early Advisory System – SEAS) utilize this methodology.

The SaWs produce daily detection products, with monthly and quarterly outlook bulletins. NOAA also provides a weekly Sargassum Inundation Report. The SEAS program produces forecasts that extend as far as eight days.

However, there are limitations on data and mats that are difficult to detect during rough sea conditions.

Sargassum in T&T

Sargassum is a year-round visitor to Trinidad and Tobago’s coastlines, predominantly affecting our Atlantic-exposed coasts on both islands.

T&T has experienced some severe sargassum events in the past, namely in 2011, 2015, and 2018.

During 2011, massive quantities of drifting Sargassum washed up throughout the Caribbean, from The Bahamas, throughout the Greater and Lesser Antilles, and Trinidad and Tobago.

2015 Sargassum Crisis

The “unprecedented” event started with a few clumps of brownish-colored seaweed washing ashore along the Mayaro coastline in early April. However, this quickly transformed into large floating mats of seaweed, which changed the southeastern and Manzanilla beaches’ shoreline into a virtual brown carpet bringing the fishing industry in the areas to a standstill.

It also drifted to coastal villages along the southwestern peninsula, blanketing the coastline of the rural fishing villages of Cedros and Icacos with mounds of seaweed that was described as, “an ecological disaster on par with an oil spill.”

In Tobago, the event was treated as a natural disaster, with nearly TTD 4 million spent on clean-up efforts by the Tobago House of Assembly. In Speyside, 1,983 truckloads with approximately 12,000 cubic feet of seaweed were removed. Mats of Sargassum also moved in on Lambeau, Rockley Bay, Bacolet, John Dial, Hope, Argyle, and Roxborough. Several hotel bookings were canceled, and events were postponed due to the seaweed event.

Mats up to two feet thick washed ashore at Pinfold Bay, King’s Bay, Hope Beach, Kilgwyn, and Little Rockly Bay. In Trinidad, east coast beaches from Cumana to Guayaguayare were affected.

2017

Aerial photos of Sargassum affecting Tobago’s coastlines. Photos: TEMA

Sargassum returned across Tobago by mid-2017, affecting both the island’s Atlantic (Windward) and Leeward coasts. These included Lambeau, Rockly Bay, Bacolet, John Dial, Hope, Argyle, Roxborough, and Speyside.

2018

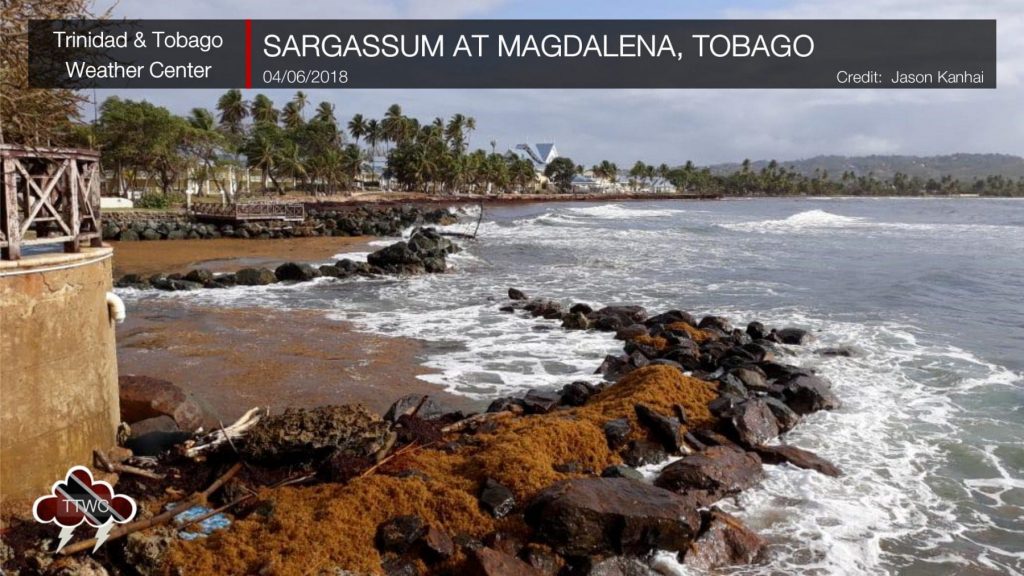

Sargassum began to pile up across Trinidad’s Mayaro coastline starting by mid-February 2018, with the seaweed observed on stretches of beach including such popular areas as Plaisance Road, Church Road, and Indian Bay.

Mounds of Sargassum were piled as high as 3 feet on the Mayaro shoreline. The seaweed adversely affected the local tourism and fishing industry due to the inaccessible beaches and the foul smell of the decaying Sargassum.

By April 2018, the Office of Disaster Preparedness and Management (ODPM) said that “significant quantities” of the seaweed had been observed off the east-southeast coast, mainly in the Point Radix, Manzanilla, and Mayaro areas.

Sargassum began to affect the coasts of Tobago by June through July 2018, with accumulations occurring in Speyside, Roxborough, and Lambeau.

Effects & Hazards

Marine Ecology

The camouflaged sargassum fish (right) has adapted to live among drifting Sargassum seaweed. It is usually a small fish (left). Some other small fish, such as this juvenile puffer (center), are also found in sargassum.

Sargassum, a floating habitat, provides food, refuge, and breeding grounds for various animals such as fishes, sea turtles, marine birds, crabs, shrimp, and more. Some animals, like the sargassum fish (in the frogfish family), live their whole lives only in this habitat.

Sargassum serves as a primary nursery area for a variety of commercially important fishes such as mahi-mahi, jacks, and amberjacks.

When Sargassum loses its buoyancy, it sinks to the seafloor, providing energy in the form of carbon to fishes and invertebrates in the deep sea, thus serving as a potentially important addition to the deep-sea food web.

Because of its ecological importance, in 2003, Sargassum, within U.S. Exclusive Economic Zone off the southern Atlantic states, was designated as Essential Fish Habitat, which affords these areas special protection.

Sargassum mats are home to more than 11 phyla and over 100 different species. There are also 81 fish species (36 families represented) that reside in the Sargassum or utilize it for parts of their life cycles. Other marine organisms, such as young sea turtles, will use the Sargassum as shelter and a resource for food until they reach a size at which they can survive elsewhere.

Commercial Uses

In St Lucia, one entrepreneur is turning it into a plant tonic, while in Barbados, a fertilizer project is underway. Sargassum has a nutrient content of about 1- 1.5% nitrogen, 0.5 – 1.5% phosphorous, and 1- 2% potassium. Composting can alleviate the usage of synthetic fertilizers. Sargassum seaweeds have essential nutrients that plants need; this can also help mitigate some of the synthetic fertilizers used.

During the 2015 Sargassum Crisis in Trinidad and Tobago, a local cocoa estate began using the seaweed as fertilizer.

There is also talk of bio-gas in Barbados depending on a regular supply of biomass and affordable collection costs. Tests have found some sargassum is high in arsenic, which rules out use as animal feed.

The seaweed has also been used to create paper products, cosmetics, skincare products, cocktail drinks, and bricks for home construction.

Disruption to Tourism

When Sargassum is present in nearshore areas (bays, beaches), venturing into the water can become dangerous and is not recommended.

When Sargassum piles up onshore, the decomposition produces hydrogen sulfide, giving off the scent of rotting eggs that repel beachgoers and tourists. In particularly severe situations, this can disrupt economies dependent on tourism.

Disruption to Fishing

Sargassum mats can stretch for kilometers across the ocean. This can prevent boats from getting into the water in nearshore areas. The seaweed itself can become entangled in fisherfolks’ nets, lines, and boat propellers.

Disruption of Marine Life

The seaweed can entangle ea turtles and dolphins, fatally preventing them from surfacing for air. While still offshore, it can smother seagrass meadows and coral reefs when it dies.

In 2015, 2 mature and juvenile hawksbill, leatherback, and green turtles died as they struggled to make it to and out of Barbados nesting sites, which lay under two to three feet of Sargassum seaweed.

In the case of Trinidad, piles of seaweed on the coasts have proved detrimental to nesting for the endangered leatherback turtles, making their trek to land and nesting onshore more difficult.

This seaweed can make it nearly impossible for turtles to dig holes to lay their eggs and hatchlings also struggle to walk on the seaweed en route to the sea. Many hatchlings have died after becoming tangled and trapped in the sargassum seaweed.

Health Hazards

Hydrogen Sulfide – When washed ashore, Sargassum will decompose. Decomposing Sargassum produces hydrogen sulfide gas, which smells like rotted eggs – giving an unpleasant smell.

Hydrogen sulfide can irritate the eyes, nose, and throat. People with asthma or other breathing ailments will be more sensitive to the effects of hydrogen sulfide. In severe situations, vulnerable groups may have difficulty breathing after inhalation.

This gas, in high concentrations, can also cause the discoloration of metal faucets and corrosion of wiring in any electronic items.

Skin Irritation – Sargassum itself does not cause rashes or stings. However, tiny organisms that live in the Sargassum like larvae or jellyfish may irritate the skin when in contact.

As of 2019, CHU Martinique has seen over 200 patients for clinical symptoms potentially associated with exposure to gaseous emissions from Sargassum decomposition. The most frequent clinical signs and symptoms include:

- General reddening and irritation to the skin and eyes – mucous membrane irritation.

- Upper respiratory tract infection with coughing and wheezing.

- Headache, moderate abdominal pain, and intestinal transit disorders.

Safety

In most cases, Sargassum mats are not hazardous to human health. Practice common sense safety if you live along the coastline or are interacting with the seaweed.

- Always supervise children at the beach.

- Avoid touching or swimming near seaweed to avoid stinging by organisms that live in it.

- Use gloves if you must handle seaweed.

- Stay away from the beach if you experience irritation or breathing problems from hydrogen sulfide—at least until symptoms go away.

- Close windows and doors if you live near the beach.

- Avoid or limit your time on the beach if you have asthma or other respiratory problems.

If workers are collecting and transporting Sargassum, they should wear protective clothing, such as gloves, boots, and gas filter half masks.

Frequently Asked Questions

Beyond the unpleasant smell, can Sargassum harm me?

As mentioned above, people with asthma or other breathing ailments will be more sensitive to the effects of hydrogen sulfide (the cause of the unpleasant smell). Sargassum can irritate the eyes, nose, and throat. In severe situations, sensitive people may have difficulty breathing after inhalation.

If you are exposed to hydrogen sulfide for a long time in an enclosed space with little airflow (like some work exposures), it can affect your health. However, hydrogen sulfide levels in areas like the beach, where large amounts of airflow can dilute concentrations, are not expected to harm health.

Can I consume Sargassum?

You should not use Sargassum in cooking because it may contain large amounts of heavy metals like arsenic and cadmium.

Is it a problem to leave it to rot on the beach?

Sargassum occurs naturally on beaches, in smaller quantities. It plays a role in beach nourishment and is an essential element of shoreline stability. For example, dune plants need nutrients from the sargassum, and sea birds depend on the sea life carried in the sargassum for food. During decomposition, there will inevitably be a smell and insects around. The experience in locations that have left the sargassum on the beach is that it will eventually get washed away or buried in the next storm, with the rain easing the smell. Leaving sargassum on the beach has proven to be the most straightforward approach, avoiding potential negative impacts associated with beach cleaning.

What can we do about it?

In embracing the challenge of sargassum, good communications between agencies and the private sector, with the press, and with locals and visitors is essential to ensuring everyone knows where clean beaches can be found.

The law does not require agencies to remove seaweed in many countries since it’s not marine debris but is a natural part of the ecosystem. Where private sector capacity exists to clean beaches, coastal managers agree on balancing the importance of sargassum for natural processes and as life-giving nourishment for beaches and seabirds, with pressure to address adverse impacts on communities. The next step is to establish clear policies about where, when, and how to clean beaches,