At this point, we’re all fatigued by the “Adverse Weather Alert.” Sometimes the “adverse weather” materializes, sometimes it doesn’t, and sometimes, as pointed out by several on social media, it seems to be a purely reactionary measure by officials.

Before delving into its effectiveness, let’s take a look at the Trinidad and Tobago Meteorological Service (TTMS) Early Warning System or EWS.

The Early Warning System

In theory, it’s a great system to warn the public about impending hydro-meteorological hazards. However, when used (as seen by the public) arbitrarily, it loses its effectiveness. Worse yet when the threat never materializes, there is the “cry wolf” situation.

To encompass the alert/watch/warning into one word, we’re going to use the word advisory/advisories going forward in this article.

What hazards do the Early Warning System Cover?

The Early Warning System is designed in Trinidad and Tobago to cover hydro-meteorological hazards such as Severe Weather & Thundershowers (i.e. Adverse Weather), Flooding, Dry Spells/Droughts, Extreme [High] Temperatures, and Hazardous Seas, in addition to already established notifications for Tropical Cyclones (Depressions, Storms, and Hurricanes).

This alert system utilizes the common alerting protocol or CAP format, which is a standard adopted by the World Meteorological Organisation and the UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. In other countries in the Eastern Caribbean that also utilize this format, tsunami advisories can also be disseminated through the CAP format.

What does the Alert/Watch/Warning Mean?

Using the Alert/Watch/Warning terminology versus the prior “bulletin” is another great feature, but only when used according to its intended time frame.

Back in April 2018, when the Trinidad and Tobago Meteorological Service rolled out the Early Warning System, the Quality Manager for the TTMS, Haley Anderson, spoke at a media conference at the Ministry of Public Utilities.

He said alerts would be issued much further in advance, such as two to five days away, when it is suspected the hazard would be a threat to this country. He explained as the forecasters become more confident, a watch will be issued closer to the time, followed by a warning when it is almost certain the hazard is going to happen.

Trinidad and Tobago Newsday, April 2018

According to the TTMS, the following are the intended lead times for their advisories:

- Alert – There is a remote possibility or possible occurrence. Beyond 2 days lead time.

- Watch – Likely or will probably occur. 12-48 hours lead time (48 hours for Tropical Cyclones).

- Warning – Observed, or almost certain/imminent occurrence. Less than 12 hours of lead time (Less than 36 hours for Tropical Cyclones).

As part of the Early Warning System, the TTMS also issues the urgency of the alerts, so citizens can take heed on the likelihood of the impending natural hazards. For alerts, it is “future”; for watches, it is “expected” and for warnings, it is “immediate.”

This is perhaps one of the most mind-boggling things about the early warning system, as for nearly every “Adverse Weather” advisory issued, regardless of lead time, it is an alert. Yes, Adverse Weather Warnings have been issued in the past – September 2018, July 2018 to name a few, but still, the timeline of alerts/watches/warnings aren’t adhered to generally.

According to the TTMS, on a recent social media post, when asked about the lead times, they responded, “some work has to be done on that aspect of the system, so only alerts are being issued at the moment.”

They further elaborated, with respect to an “Adverse Weather” advisory being issued for every tropical wave, “Theoretically, you could have a season with an alert every week or you could have a season with an alert once a month. Basically, it all comes down to the background setup at the time of the passage of these waves, which can vary a lot. Each passage has multiple scenarios that could play out, however, once there is the likelihood of a scenario being significantly impactful for some areas, an alert is issued. If you check out the info-graphic attached (see above) to the current alert, you will see that most people can go about their normal routines, but some areas can be negatively impacted. In these cases, we ask emergency responders and the public to be on the lookout.”

The Risk Level

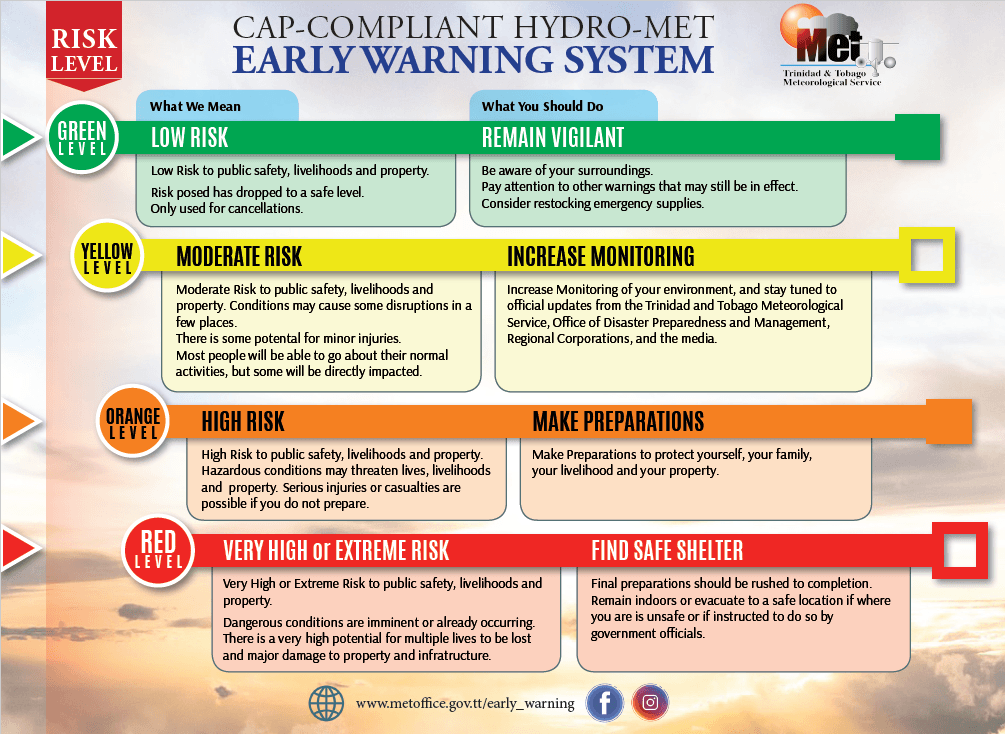

Adding another dimension to the Early Warning System, the TTMS implemented a Traffic Light System. The framework for this system is clearly laid out and is generally adhered to.

The Green level is used when there is low risk to public safety, generally when an advisory is cancelled or more recently “discontinued.”

The Yellow level is used, perhaps the most frequently, where there is a moderate risk to public safety, livelihood, and property. At this level, conditions may cause disruptions in a few places and there is the potential for some minor injuries. Most of the public will be able to go about their normal activities but some will be directly affected.

The Orange level is used when there is a high risk to public safety, livelihoods, and property. Hazardous conditions may threaten lives, livelihoods and properly. Serious injuries and casualties are possible if you do not prepare.

The Red level is used when there is a very high or extreme risk to public safety, livelihoods, and property. Dangerous conditions are imminent or already occurring. There is a very high potential for multiple lives to be lost and major damage to property and infrastructure.

Other Features of the EWS

For advisories to be CAP-compliant, they also need to include other bits of information. This includes the validity time, meaning the date and time of issuance, when the advisory goes into effect and when it ends.

In addition, there needs to be the response type, instructions for the appropriate response by both citizens and officials. This is tied to the risk level (see above).

Lastly, the description of the hazard event and the area description. The area description is also shown on a map on the TTMS’ website.

What Triggers An Alert/Watch/Warning To Be Issued?

This is where it gets a little fuzzy.

In the case of Tropical Cyclones (Tropical Depressions, Tropical Storms, and Hurricanes), it’s easier to determine, as seen below. What needs to be stressed for Tropical Cyclones is that these watches and warnings are wind-based only. Storm surge, heavy rainfall, hazardous seas may occur well before the peak winds arrive and well after the peak winds end.

The lead times for these watches and warnings are well established across the North Atlantic Basin and are generally issued by the local meteorological office/government based on the advice from the National Hurricane Center.

For all the other hydro-meteorological hazards, (Severe Weather & Thundershowers (i.e. Adverse Weather), Flooding, Dry Spells/Droughts, Extreme [High] Temperatures, and Hazardous Seas), at least publicly, there is no minimum threshold for an alert/watch/warning issuance.

However, it generally is understood that this is a risk-based system. What that means is as soon as there is a risk of, for instance, adverse weather, the alert level will be raised. The TTMS’ position is that “it’s better to be prepared rather than be caught off-guard, and will issue a Yellow from the instance we (TTMS) suspect there’s a risk.” says Haley Anderson (in the comment section), Quality Manager at the TTMS.

Mr. Anderson continued, “As you will know, forecasting the exact way the weather will manifest itself is highly treacherous. The TTMS has decided to inform the public of its understanding of anticipated weather IN SPITE OF KNOWING it may not pan out exactly the way we think so at least people are paying more attention (hence the instruction “monitor the weather and updates”).”

This is a fair position. As most persons in Trinidad and Tobago always look to the TTMS after a severe street/flash flooding event and say “Where was the warning?” However, it also lends itself to the “cry wolf” scenario, where these yellow level alerts are issued but the threat never materializes.

2019 Advisories Issued by the TTMS Early Warning System

- June 1st-2nd, 2019 – Adverse Weather Alert – Yellow Level for T&T. There were reports of wind damage and fallen trees. This was due to the passage of Tropical Wave 02.

- June 16th-19th, 2019 – Adverse Weather Alert – Yellow Level for T&T. This alert was extended three times. This was due to the passage of Tropical Waves 08 and 09, producing isolated rainfall totals between 50-100 millimeters produced street flooding across parts of Trinidad, with numerous power outages and downed trees resulting from gusty winds.

- June 27th-28th, 2019 – Adverse Weather Alert – Yellow Level for Eastern Coastal Waters and Trinidad. This was due to the passage of Tropical Wave 13. Inclement weather brought gusty winds bringing down trees, causing overhead electrical wires to spark, and generating locally rough seas. Street flooding was reported across several parts of San Fernando with street flooding also occurring across several parts of the Penal Rock Road.

- June 30th to July 1st, 2019 – Adverse Weather Alert – Yellow Level for Trinidad. Street flooding and gusty winds occurred across Trinidad.

- July 5th, 2019 – Adverse Weather Alert – Yellow Level for T&T. This is one of the Adverse Weather advisories that were issued after much of the worst of the weather passed through prior to issuance. This Adverse Weather Alert was discontinued 6 hours after going into effect. This was due to the passage of Tropical Wave 15.

- July 15th, 2019 – Adverse Weather Alert – Yellow Level for Northern Trinidad, Tobago. Beyond an isolated thunderstorm affecting Tobago during the alert period, this was another one of those alerts that was issued where much of the adverse weather did not materialize across the areas under the alert and was issued past the period of inclement weather.

- July 17th, 2019 – Alert not issued – Severe street flooding occurred across San Fernando and Western Trinidad with wind damage reported in Tobago. This activity was due to Tropical Wave 22 and the ITCZ.

- July 27th-28th, 2019 – Adverse Weather Alert – Yellow Level for Trinidad and Tobago and was extended into the Sunday evening. This activity was due to Tropical Wave 29. However, much of the “adverse” weather occurred prior to the issuance of the alert and very little significant activity occurred during the alert period. In fact, the following day, July 29th, severe street/flash flooding occurred across the East-West Corridor and no alerts were in effect.

- August 5th-6th, 2019 – Adverse Weather Alert – Yellow Level for Northern & Central Trinidad. This was due to the passage of Tropical Wave 32. This was another alert that was issued after inclement weather began across the islands, triggering street flooding, downed trees, and landslides. However, adverse weather did continue throughout the alert period.

- August 7th, 2019 – No alerts were issued for T&T, but street flooding occurred across parts of Western Trinidad and a landslide occurred in Tobago. This was due to the passage of Tropical Wave 33.

- August 13th-15th, 2019 – Adverse Weather Alert – Yellow Level for Trinidad, then included Tobago, and then extended. A severe downburst event caused several reports of wind damage across Southwestern Trinidad. This activity was due to the passage of Tropical Wave 35.

- August 17th, 2019 – Adverse Weather Alert – Yellow Level for Trinidad and Tobago. This was issued due to Tropical Wave 36 moving across T&T, but much of the convection associated with this wave moved north of Trinidad, and mainly affected Tobago. This alert was discontinued several hours after going into effect. No inclement weather reports were recorded.

Alert Effectiveness

More often than not, the Trinidad and Tobago Meteorological Service has gotten it right, when alerts were issued. Of the 10 Adverse Weather Alert periods for 2019, 5 of those were forecasted accurately and 1 was forecasted slightly later than the actual start time.

It is still concerning that there were three times this year when adverse weather occurred across (mainly) Trinidad, but also Tobago and an advisory was not in effect. In addition, there were 4 times an alert was in effect by the TTMS but no severe weather occurred.

For those that argue the TTMS is reactionary versus proactive, based on their issuances of alert, they have a valid argument. For four (4) of the alert periods, year to date, these alerts have been issued after inclement weather occurred or while it was ongoing.

How do we improve?

Perhaps one of the easiest problems to fix is appearing less reactionary and more proactive on the TTMS’ behalf. This comes from issuing alerts after adverse weather has impacted a portion of the country. This reduces the public’s confidence in the ability of the TTMS to forecast.

However, fixing this problem also ties into the next, dealing with the crying wolf syndrome. When the TTMS issues an Adverse Weather Alert (or another advisory) and no adverse weather materializes, it creates a sense of complacency when actual adverse weather occurs and the TTMS accurately forecasted the event.

The population of Trinidad and Tobago needs to understand that this country has an incredibly high flood vulnerability. Simply put, it does not take much for (mainly) Trinidad to flood.

Trinidad and Tobago has heavy showers and thunderstorms. It’s part of living in a tropical area. These heavy downpours overwhelm what drainage exists from time to time and produce street flooding. In severe cases, very gusty winds occur.

Thunderstorms also frequently affect Trinidad and Tobago, particularly during the wet season. This not only brings heavy rainfall but gusty winds that down trees, bring down utility poles and lines, damage roofs and can threaten lives.

Thunderstorms and heavy showers occur on a near-daily basis across parts of Trinidad during the wet season. They are fairly common to Trinidad, Tobago and the vast majority of the world. In fact, there is, on average, 2000 of these storms occurring simultaneously at any given time around the globe.

In Trinidad, these thunderstorms generally occur during the late morning through the afternoon, particularly during the wet season. Any area in Trinidad can experience, on average, 30 to 40 thunderstorms annually. On rare occasions, as many as two to three a day in a given area.

When particular weather features traverse the region – tropical waves, tropical cyclones, surface troughs, mid- and upper-level troughs, and the Inter-Tropical Convergence Zone, thunderstorms can be abundant.

Thunderstorms bring most of our rainfall and nearly all of our street/flash flooding events. Torrential downpours, such as the one today, can produce upwards of 20-30 millimeters of rainfall within an hour.

In addition, these thunderstorms can produce severe winds up to and in excess of 65 KM/H across localized areas of the country.

Stationary thunderstorms, such as those that caused the Divali 2017 floods, can produce upwards of 100 millimeters in one to two hours. Thunderstorms can last from 30 minutes to as long as two hours, depending on the speed of low to mid-level winds. More prolonged thunderstorms begin to trigger different types of flooding – street, then flash and lastly riverine flooding.

So how should it be handled when it comes to issuing alerts?

Is an alert going to be issued for every tropical wave and every street flooding event? Are alerts now only going to be used for very severe events that produce flash and riverine flooding? What will happen to the severe street flooding events and localize severe wind events?

Ultimately, these decisions are up to the Trinidad and Tobago Meteorological Service. Issuing an Adverse Weather Alert for every tropical wave will breed complacency and resentment to the TTMS who may have lost worktime or cancelled an event because of the alert when in actuality, most of the adverse weather moves north or away of Trinidad and Tobago

Perhaps, a more pointed advisory needs to be issued, fully utilizing the alert/watch/warning system to pin-point the areas that have the highest likelihood of experiencing thunderstorms and heavy showers with respect to street flooding, gusty and severe winds, etc.

However, this is easier said than done. Trinidad and Tobago’s local climate is very volatile. This is why forecasters can’t necessarily pin-point far in advance if it’s going to rain in a highly specific area. Trying to forecast the effects of day time heating, sea breeze convergence, the overall prevailing winds, our topography influencing low-level winds, moisture through the atmosphere (to name very few factors) is difficult when conditions are constantly changing, and not in a homogenous way.

It’s even more difficult when global models can’t accurately parameterize these features for our small area, and reduce T&T to a few pixels on model outputs.

It’s not an easy problem to fix, but we hope that the forecasters at Trinidad and Tobago Meteorological Service, the only body in Trinidad and Tobago responsible for issuing hydro-meteorological alerts, can fix it soon.