A fault is (generally) a flat fracture or break in a section of rock. These can be relatively small, which you can see in outcrops of rock to thousands of kilometers long, usually along plate boundaries. Faults could be as long as hundreds of kilometers, such as the El Pilar Fault that runs across Trinidad and Northeastern Venezuela to less than a millimeter. It is important to note that faults generally are not one single fracture within a rock. Hence, geologists and geophysicists typically refer to fault zones.

An earthquake occurs when there is a release of stress within a layer of rock, usually at a zone of existing weakness within a rock. Earthquakes don’t necessarily happen on existing faults, but once an earthquake occurs, a fault will exist in the rock at that location.

Generally, there are three different types of faults: normal, strike-slip, and reverse. It is common to see a combination of these three types in reality, though purely normal, reverse, and strike-slip faults do exist.

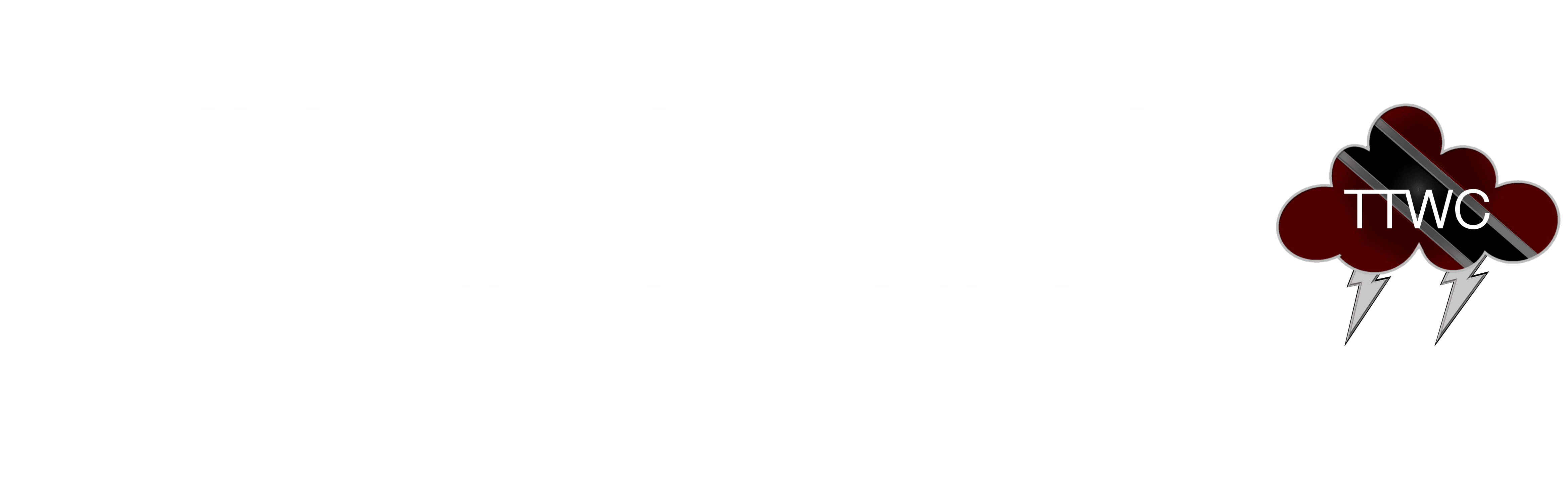

Normal Faults

Normal faults generally form in areas where rock is being pulled apart or extended. At a normal fault, rock drops on one side of the fault relative to the other side of the fault. The dropped section of rock is called the footwall, and the other side that is relatively higher is called the hanging wall.

Normal faults occur across much of Trinidad and Tobago, typically near regional (large) strike-slip faults, such as in the Gulf of Paria. Large normal faults also exist off the Eastern and Northern Coasts of Trinidad.

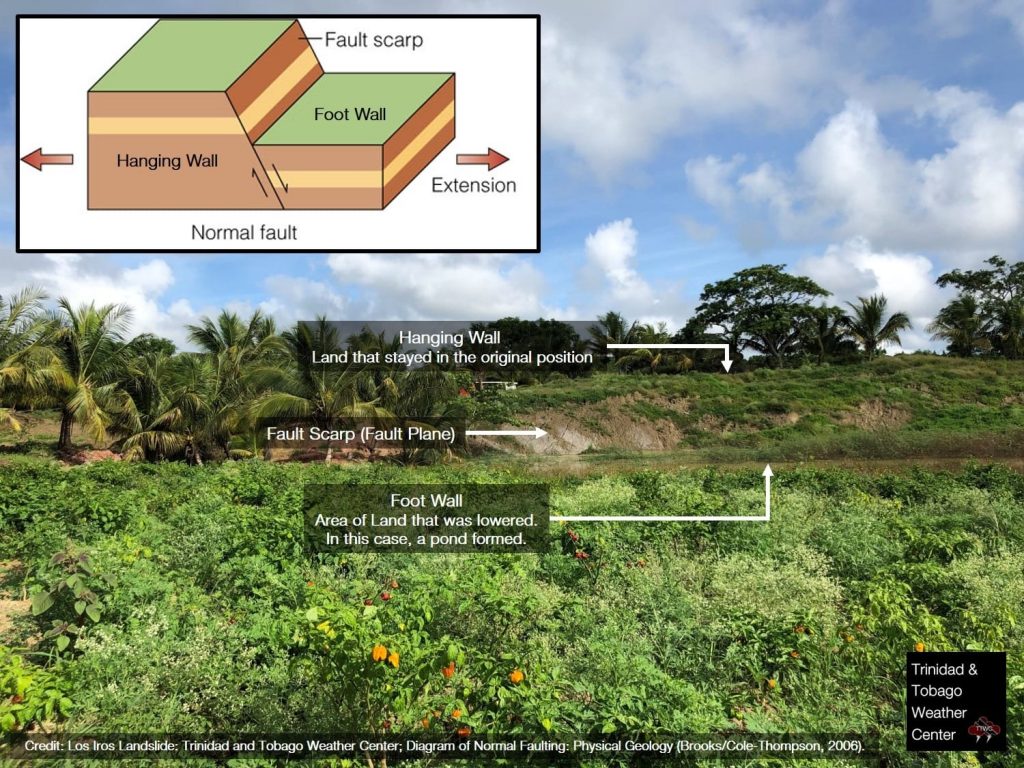

Strike-Slip

Strike-slip faults are when one area of rock slides past another laterally. These faults can be subdivided into left-lateral (sinistral) or right-lateral (dextral) strike-slip faulting.

Several large faults across Trinidad are strike-slip in nature, including the El Pilar Fault, which runs south of the Northern Range across Trinidad and into the Northwestern Paria Peninsula of Venezuela. Other notable strike-slip faults are the Central Range Fault and the Los Bajos Fault.

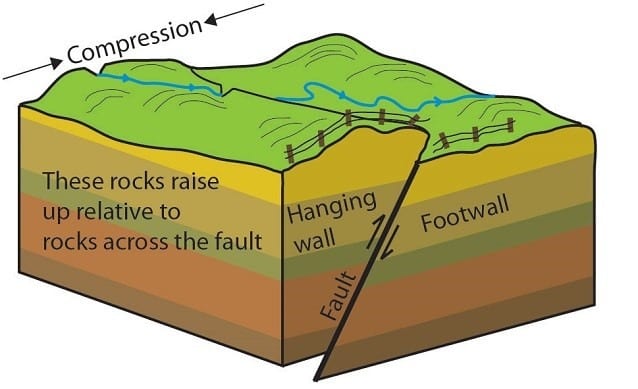

Reverse & Thrust Faults

Reverse faults tend to occur in areas where the crust is compressed together, such as in convergent plate boundaries (below). This type of fault is essentially the opposite of a normal fault. Instead of an extensional force acting on a slab of rock, a compressive force acts instead. This causes the stressed slab of rock to fracture, resulting in one area of rock rising above the other area of rock along a fault plane.

Reverse faults are responsible for some of the most damaging and powerful earthquakes. These earthquakes are dubbed megathrust earthquakes. Reverse faults can also be subdivided into two sub-types: thrust, where the dip of the fault is 45 degrees or less, and overthrust, where the dip is less than 15 degrees.

Since 1900, all earthquakes of magnitude 9.0 and greater have been megathrust earthquakes. No other type of known terrestrial source of tectonic activity has produced earthquakes of this scale.

Reverse faults are associated with earthquakes of magnitude 8.0 or more generally. Strike-slip faults can produce major earthquakes up to approximately magnitude 8.0. Earthquakes associated with normal faults reach an upper limit at approximately magnitude 7.0.

In real life, faulting is not as clear-cut as theory makes it out to be. Usually, faults are not solely up and down or side to side movement. There is typically a combination of fault movements occurring simultaneously. Trinidad and Tobago is a perfect example of this, where all three major fault movements – strike-slip, reverse, and normal – co-occur or in tandem.

It is important to note that across Trinidad and Tobago, the longer faults (i.e., the faults that have the potential to produce the largest earthquakes) at shallow to intermediate levels are strike-slip in nature. Hence, the largest possible quake near Trinidad and Tobago is usually near its maximum magnitude of 8.0. However, reverse faulting occurs just north and east of Trinidad and Tobago. Worst-case modeling shows that quakes up to magnitude 8.5 are possible, and as a region, we should be prepared since it is not a case of if this quake occurs but when.